The Silver Persian has long been referred to as the “Rolls Royce” of the cat world. The look is timeless and elegant, and they have always been described as regal and exquisite in appearance. It is a “breed” of classic, incredible beauty, considered by many to be the most beautiful Persian colour, if not “the fairest of them all.” Along with the elegant Golden Persian, they have always been a challenge to breed, and silver and golden breeders are a dedicated and determined group. Most have found it more productive to specialize: almost without exception, the top winners of each era have come from catteries that have bred only these colours. Breeding silvers and golden's in addition to another colour or breed means keeping two or more sets of cats.

The History

The earliest documentation of silvers shows “Chinnie,” born in 1882 in England. While no pictures of her have been found, there was one of her famous grandson, “Silver Lambkin.” Some of the pedigrees of our present day silvers have been traced back to Lambkin. There was little record keeping in the early days, but as time went on people paid more attention to documenting their breeding. These records showed that other colours, often blues and tabbies, were used in the breeding of silvers. Silvers also appeared in the pedigrees of Persians of other colours. There is no record to show when silvers were accepted by the Cat Fanciers’ Association, so it is reasonable to assume they were among the original colours bred when this association was organized in 1906. Silvers had been imported into the United States from England before that date.

The Golden Persian does not have as long a history as does the Silver Persian. The golden colour is recessive to silver, and for many years before this colour was accepted, “odd colours” kittens occasionally popped up in “colorbred” silver litters (see Breeding for Golden's). Most often these kittens, then referred to as “brownies,” were placed as pets. By the 1960s a few interested breeders were working with them. The beauty of their golden coats with the contrast of their vivid green or blue-green eyes attracted more and more dedicated breeders,

The Division

Silver, golden, smoke, and cameo Persians have been subject to more division changes than any other colour. The Shaded Division consisted of chinchilla silvers, shaded silvers, and smokes until 1961; at this time, cameos were accepted and added to the division. In 1965, the smokes were taken out of the Shaded Division and given their own division: the Smoke Division. The next change came in 1976 when chinchilla golden's and shaded golden's were accepted in the Shaded Division.

Early Persians of all colours bore little resemblance to today’s Persians. It was some time before the concept of “color breeding” came into being. With selective breeding, silver breeders had nearly eliminated tabby markings and leg bars by the mid-20th Century, therefore colour breeding became a must. Silver breeders were criticized if their cats were not colorbreed; however, there was no agreement on how many generations were required for a silver to be considered a “colorbred” cat.

Colour breeding was a necessity for many years in order to maintain the beautiful trademark colouring of the silver Persian. The gene pool was small, and certain physical characteristics appeared to be associated with the silver colour: the cats produced were generally lighter in bone and eventually, smaller in size. Additional colours and patterns of the other Persians were developed over the years resulting in a larger gene pool, while the gene pool of the silvers remained the same. This led to an interest on the part of some breeders to include other colours in their breeding programs.

The introduction of solids into a golden program to improve type and bone causes the same problems that it does in a silver program, if not more of them. It muddies the coat colour and spoils the eye colour; it also causes more tabby markings in a colour that has not yet eliminated these markings. Silvers, having been bred in the United States for a century, have had a long head start on golden's, whose breeding history here is less than half of that time. Silvers were being bred before 1900, but golden's were not seriously bred until the 1960s. What was once written about silvers is now also true for golden's: “You’ve come a long way, baby!”

The eye colour in silvers and guldens' has always been considered very important, which is why the standard is specific. It clearly states: “Eye colour: green or blue-green. Disqualify for incorrect eye colour, incorrect eye colour being copper, yellow, gold, amber or any colour other than green or blue-green.” All silver and golden breeders want this eye colour in their cats. This may be difficult to attain, but it does not change the fact that this is the standard, although some are willing to accept less. A silver or golden with incorrect eye colour may be valuable in a breeding program, but it does not belong in the show ring.

Some breeders and judges say that they began by breeding silvers and gave up because they are too difficult. Golden's are even more difficult to breed to the standard than the silvers. With some exceptions, they are years behind silvers in type, which may be attributed to the small number of breeders working with them until recent years. While silvers have variations in the amount of tipping, they do have a white undercoat with black tipping – one shade of white and one shade of black, to simplify the description. The golden's are quite different. The golden standard calls for the undercoat to be cream, and the tipping black. While a cream cat with black tipping and green eyes would be beautiful, that is not a true golden. It would be more accurate to say, quoting Judith Legg, that “the undercoat is usually cream colours and sometimes it’s gray with seasonal variations. The ‘overcoat’ of guard hair is ticked. Each hair shaft is banded with yellow, rust and dark brown or black. Golden's, including chinchillas, have tabby M’s on their foreheads, and dark spines and dark tail tips.” This probably explains why there have been many variations of the golden colour. The colour has ranged from pale amber to bright red-gold to the less desirable brownish-gold. Early golden breeders had tried for so long to have golden's accepted that they did not want to quibble over this colour description; however, this was not what had been submitted as their standard.

Rarely do two golden's have the same shade, even from the same litter, and the coat colour can change until the cat is five years of age or even older. Some golden's are born with wonderful, rich colour; some take two to three years to develop. The colour of the undercoat can change with the seasons of the year, even achieving a gray, muddy colour at certain times of the year. For years, further frustration came from the fact that if a golden had good colour, it lacked type and was not showable; if it had type, the colour was poor, so it also was deemed not showable. While some judges have bred silvers and appreciate the difficulties, no judge has bred golden's, so they have not experienced all the variations and changes in colour. Nearly all golden breeders feel that if a silver and golden of comparable type are in competition, the silver is more likely to be chosen. There are so few golden's' shown, usually only one golden in the ring, that judges have rare opportunities to compare their colour.

Many golden's have been incorrectly registered and shown in the wrong colour class. An apricot golden has been shown as a chinchilla golden simply because of its light colour, not because of the appropriate amount of tipping. A darker golden colour was more apt to be shown as a shaded golden simply because it was dark, with less attention given to the amount of tipping. Whether golden or silver – colour class has been defined by the amount of tipping, not the colour of the undercoat.

The Look

The 1950s, ’60s, and ’70s produced many beautiful and very competitive silvers, no different from Persians of other colours in type it was by the late 1970s that blacks had developed a different “look” and shorter noses than some other colours; however, the silvers were as good or better than the whites shown at the time. Silver breeders were breeding selectively to improve and set type. When compared to some of the other colours, silvers improved more quickly in doming, towhead, and ear size. Unfortunately, this selective breeding further limited the already small gene pool.

From time to time, some breeders talked about the possibility of a “different” standard for Silver and Golden Persians; however, most feel that good silvers and golden's meet the standard as it is written. It has not been the standard or the cat at fault, but more likely the way the standard has been interpreted over the years. Sometimes we hear a cat praised for having “no nose.” The standard calls for “a short nose”; how short is not defined, but it does not say “no nose!” It describes a “break,” but does not specify how deep the break should be. What is far more specific in the standard is the location of the break, described as “centered between the eyes.” Until the standard becomes more specific, silvers and golden's should not be penalized for not having noses as short, nor breaks as deep, as some Persians of other colours. During a discussion while judging silvers, one judge stated his opinion that silvers (and golden's) should have a nose “as broad as it is long.” This meets the description in the standard for a “broad” nose, as well as contributing to the overall balance of the cat. While silvers and golden's may not have noses as short as some Persians of other colours, they have met the criteria of “as short as it is broad,” and they are more likely to excel in round doming and small, well-set ears. Their skulls have been smooth and round, without the ridges and flatness often found in Persians of other colours.

Silvers and golden's may never look exactly like other Persians. Breeders have used careful selection to improve boning and head type, but the “extreme” genes might not be there. Occasionally a kitten has been born with the “extreme” type similar to that of a solid Persian, but these cats have not consistently reproduced that look. Outcrossing to solids has resulted in some unusual colours, and by the time coat and eye colour have been regained, type has usually reverted to what has been known and admired as “the silver look.” Perhaps, as in the Peke-face Red Tabby standard which has an “allowance” for a difference in type, an allowance could be included in the Silver/Golden standard so that these beautiful cats do not lose their unique look.

Silvers generally have lower birth weights and leave the nest box quite early. Although they mature sexually at an early age, they do not look their best until they are three to five years old. Some silvers and golden's are smaller in size and lighter in bone when compared with the other Persians. The phrase “medium to large” in the standard has not been defined, and size is relative. The standard also says “Quality the determining consideration rather than size.”

Silvers and golden's are outgoing cats with unique personalities; they are intelligent, affectionate and people-oriented lap cats. While they are wonderfully decorative Persians, they are not “couch potatoes,” as Persians have often been described. You will seldom find these colours dozing on grooming tables in a show hall, as you often see other Persians. They are sensitive, so they need to be socialized from an early age, and they do not take well to isolation and confinement. Many have profuse coats, and some have the difficult-to-groom “cotton candy” coat, but all seem to have fine textured hair that breaks easily. They may have more sensitive skin. All of this means that grooming had best be started early and done gently to prepare them for the care required to keep the long, flowing coat at its breathtaking best.

The Unique Silver and Golden

Silver and golden breeders have worked very hard to meet the challenge of “type” to produce beautiful, well-balanced Persians. There are variations of “the look” throughout history, but we hope the unique look of silvers and golden's will always be there. When one thinks of silvers and golden's, one pictures a cat with a wide-open, sweet expression with large, round eyes of a luminous green or blue-green. The ears are small with the wonderful round doming that seems to be a silver and golden trademark. The nose is short and broad, and this lovely round head, framed by full ruff, is attached to a short, cobby body with a long, flowing coat.

All about the colour,history,genetics:

SILVER AND GOLD: SMOKE, SHADED AND TIPPED CATS

Copyright 2003-2010, S Hartwell

There are a whole host of terms used to describe the different smoke, shaded and tipped cats. Different terms are used depending on whether a cat is longhaired or shorthaired. A number of terms are historical, but can still be found in print. Where necessary, I have included the various alternative names.

Smoke, shaded and tipped are all forms of tipped colouration - the colour is restricted to the hair tip while the shaft is either white/ivory (silver series) or golden (golden series). Shading causes the normally yellow-brown agouti band to be both lighter in colour and wider, starting closer to the root and ending nearer the hair tip than in tabby cats. The tipping colour is known as the top-colour, while the pale colour of the hair shaft is known as the undercolour. These patterns are most striking on the eumelanistic colours (black, blue, chocolate, cinnamon, lilac), because of the contrast between pattern colour or top-colour and the background or undercolour. Shading and silver also occurs in reds and creams which are sometimes termed cameos.

Chinchilla (also known as "shell") is the lightest tipping. Here, only the hair tip is coloured and the hair shaft is silver. This gives the cat a sparkling appearance. For many cat fanciers, the Chinchilla Persian Longhair (Silver Chinchilla) is the epitome of the tipped cats. It has black tipped fur on a white undercolour. The best known shorthaired equivalent is the Burmilla, part of the Asian group. Because Chinchilla cats are genetically tabby, faint tabby markings can sometimes be seen on kittens. In shorthairs, this pattern is known as "tipped".

The next degree of tipping is "shaded". The colour extends further along the hair shaft, usually about half way. The colour is darkest on the back, creating a mantle of shading. Shaded silvers are the "black" form; but the shading can be a variety of colours. Shaded Silver lies between the extremes of Silver Tabby and Chinchilla and is commonly produced by mating a Silver Tabby to a Chinchilla. The amount of tipping is variable, ranging from a poorly-defined Silver Tabby to a dark Chinchilla.

Smoke is heaviest degree of tipping. The pale undercolour is reduced to a small band near the hair root. A smoke longhair often appears to be solid coloured with a pale ruff or frill. In shorthairs, smoke varieties appear solid colour until the coat is parted or the cat is in motion, exposing the undercolour.

In genetic terms, the silver tabby is identical to the silver undercoated cats but the pattern is dissipated due to the restriction of pigment to the tips of the hairs. Silver tabbies occur in ticked, classic, mackerel and spotted patterns which are described in Striped and Spotted Cats.

EARLY TIPPED AND SHADED CATS

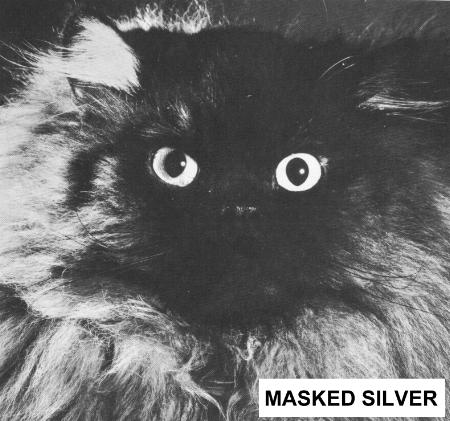

The first chinchillas, shaded and smoke cats were Persian Longhairs with black (less frequently blue) tipping or shading on a near-white undercoat. These were the Black Smoke, Chinchilla (also known as the Self Silver) and the Shaded Silver. Early Chinchilla and Shaded Silver cats were derived from silver tabbies and were less well differentiated than their modern counterparts - some early Chinchillas might today be classed as poorly defined Shaded Silvers; some also had distinct tabby markings. Orange-eyed Shaded Silvers were originally preferred and are now known as Pewters or Pewter Tipped. For a while the Masked Silver was bred - this was a Shaded Silver Persian with darker face and paws.

Silver-undercoated Persians appeared very early on in the days of the cat fancy. Smoke Persians were described as far back as the 1860s and were believed to result from mating between blacks, blues and whites. In 1872, Weir described a cat as "a beauty was shown at Brighton, which was white with black tips to the hair, the white being scarcely visible unless the hair was parted." The Smokes soon got a class of their own and their numbers rapidly increased. In Britain, dark Smokes are preferred, while American cat fanciers seemingly prefer lighter colour cats.

At the British National Cat Show in 1879, one of the entrants was described as "a strangely graduated grey". Since the Smoke was already familiar, this was most likely a Shaded Silver.

The origin of the Chinchilla Persian as a breed lies in a female cat called Chinnie, born in 1882. Silver Tabbies and Black Smokes were already known at that time. Chinnie was probably either a Silver Mackerel Tabby or a Spotted Tabby Longhair (the spotted pattern is dissipated by the long hair) and would have had weak markings (heavy by modern standards). Her exact ancestry is unknown though it includes prize winning grandparents on one side and a stray tomcat on the other. Chinnie was evidently unusual enough for interested parties to want to breed similar cats from her. She was mated to Fluffy I who was a very pure Silver with undecided tabby markings" (might also have been Chinchilla).

Sadly, many of Chinnie and Fluffy I's offspring died or strayed, and Fluffy I himself vanished in 1886. However one of their descendants, Beauty, was mated to a Smoke and produced the first recognisable Chinchilla in Champion Silver Lambkin who practically set the standard for the breed. The Chinchilla was recognised (got its own class) in 1894. Beauty continued to produce kittens and her descendants were mated to blues, silver tabbies and others. Blotched tabby, mackerel tabby and dilution were introduced into the gene pool from those very early days. Both tabby patterns can be seen in newborn kittens.

In 1903 Frances Simpson described Chinchilla shading as "a short of bluish lavender to the tips of the coat", and "delicate tips of silvery-blue". Breeders of the time describe it as "palest silver, lavender tint and lighter - in fact practically white - at the roots " and "pure silver of a bluish tinge". In 1907, the Chinchilla was also known as the Self Silver "A good self-silver has fur that is white at the roots and shades softly to a faint grey at the tips. The colour is rather that of old-fashioned silver lustre ware than of modern silver. The ideal self-silver must have neither markings nor shadings, nor must there be any black tips to the hair, either oh the back of in the tail or elsewhere". Only in 1930 did the standard refer to the tipping as "black".

Early Chinchillas had a range of levels of tipping and some confusion as to how much tipping was ideal. Orange eyes were preferred and in 1895, "Fur and Feather" carried an article regarding a green-eyed Chinchilla, "It is useless to think of exhibiting her on account of her green eyes". Green eyes later became a standard - and distinctive - feature of Chinchillas.

In 1900 the Silvers class was split into Silver Tabbies, Chinchillas (light tipping) and Shaded Silver (heavy tipping). Then, as now, there were many cats which fell somewhere between tipped and shaded, plus different judges had different ideas as to where the line should be drawn. The same cat was sometimes rejected from both classes (due to different judges' opinions) or was sometimes entered into both classes and won in both! The Chinchilla and Shaded Silver classes were combined to prevent confusion.

In 1926, after a curious cat ("a mixture of colours") owned by Mrs Boutcher won the Any Other Colour class, Lord Sylvester suggested the starting of a new breed called "Marked Silvers". The suggestion was not taken up. The cat was likely a silver tabby or shaded silver with markings of some colour other than black. In 1927, HC Brooke commented that some 50 years previously, there existed a pretty variety of short-hair tabby that was, in 1927, quite extinct. The ground colour was a creamy tint and the markings were always rather narrow and were reddish-brown. Since "sandy-coloured" or "lemony" red tabbies were frowned upon by cat fanciers, quite possibly this was a red-silver tabby. Red and cream Chinchillas appeared in the USA in 1934 through breeding Silver Chinchillas to Red Self Persians.

In 1951, Soderberg wrote wrote that the Chinchilla was unsuited to living in industrialised town! "It is a light-coated cat which is perhaps hardly suitable to the soot and grime of large industrial towns, but it is doubtful whether it needs much more attention than its darker-coated fellows."

In the 1990s, breeders were concerned that Chinchilla cats were becoming ultra-typed like other Persians. Traditionally, the Chinchilla retained the longer muzzle. In America this resulted in a new breed classification, the Sterling, for the traditional-type Chinchillas. Older-style Chinchillas are more popular with members of the public, but the showbench Chinchilla seems to be moving inexorably towards the squashed-in look of other Persians. Outcrossing to other, already ultra-typed, Persian varieties is losing the old Chinchilla look. The photos below show cats of both types.

|

Old-Style Chinchilla

|

Modern Chinchilla

|

The Burmilla is a tipped silver cat of Asian/European Burmese type. Burmillas arose in 1981 as a result of an accidental mating of a lilac Burmese female and a Chinchilla male. This produced four Black Shaded Silver kittens of Burmese type and with a short, dense coat. The following year, there was a planned mating of a Blue Burmese female with the same Chinchilla male. These were the founding cats of the Burmilla variety although there have been a number of Burmese-to-Chinchilla matings since then in order to widen the gene pool. The Burmilla was recognised by FIFe in 1994. Although a relatively young breed, it is already extremely popular. In addition to the Burmilla there are also Asian Smoked and Asian Shaded Silver cats in a variety of different top colours.

A slightly different form of tipped fur is found in the Chausie, a breed derived from hybridising F chaus (Jungle Cat) with the domestic cat. Black Chausies with silver tipped fur occur and this is belived to be a form of black agouti rather than smoke/shaded or chinchila.

THE EARLY COLOURS

Tipping is not restricted to black. It can occur in any of the solid colours. The naming convention is given in the table below. Red on silver and cream on silver are also early developed colours and hence have a number of synonyms! The term "shell" was used to describe the cat having a shell of colour rather than a solid (to-the-roots) colour. "Cameo" described the type of red - similar to the colour of old cameo necklaces - with "Cream Cameo" (pictured below) simply meaning a paler form of this.

The tortoiseshell pattern can also occur on a pale undercoat, giving us the Tortoiseshell Chinchilla (Shell Tortoiseshell, Silver Tortoiseshell), the Shaded Tortoiseshell (Tortoiseshell Shaded Silver) and the Smoke Tortoiseshell, (Tortoiseshell Smoke). Tortoiseshell tabby (patched tabby) also occurs on the silver undercolour e.g. the Silver Patched Tabby (Silver Tortoiseshell Tabby).

|

THE EARLY COLOURS AND A CONFUSION OF NAMES

|

|

Full colour

|

Chinchilla = Silver/Silver Chinchilla (shorthair)

= Tipped/Black Tipped

Shaded Silver

Black Smoke

Silver Tabby

Tortoiseshell Silver Tabby (Patched Silver Tabby)

Silver Ticked Tabby (Usual Silver Abyssinian/ Somali)

|

Red Chinchilla = Shell Cameo/Red Tipped

Red Shaded (Silver) = Shaded Cameo

Red Smoke = Smoke Cameo

Red Silver Tabby = Cameo Tabby

Red Silver Tortoiseshell/Tortoiseshell Tabby

Red Silver Ticked Tabby (Red Silver Abyssinian/Somali)

|

|

Broken Full Colour

|

Tortoiseshell Chinchilla = Shell Tortoiseshell/Silver Tortoiseshell

Shaded Tortoiseshell = Tortoiseshell Shaded Silver

Smoke Tortoiseshell = Tortoiseshell Smoke

|

|

Dilute

|

Blue Chinchilla/Blue Tipped

Blue Shaded Silver

Blue Smoke

Blue Silver Tabby

Blue Silver Tortoiseshell/Tortoiseshell Tabby

Blue Silver Ticked Tabby

|

Cream Chinchilla = Shell Cream Cameo

Cream Shaded (Silver) = Shaded Cream Cameo

Cream Smoke = Smoke Cream Cameo

Cream Silver Tabby = Cream Cameo Tabby

Cream Silver Tortoiseshell/Tortoiseshell Tabby

Cream Silver Ticked Tabby

|

|

Broken Dilute Colour

|

Blue Cream Chinchilla = Shell Dilute Tortoiseshell

Blue Cream Shaded = Shaded Dilute Tortoiseshell

Blue Cream Smoke = Smoke Dilute Tortoiseshell

|

THE NEWER COLOURS

Luckily the newer colours follow a general formula without too many confusing synonyms e.g. Chocolate (Chestnut) Chinchilla, Lavender (Lilac) Shaded Silver etc.

[colour-name] Chinchilla

[colour-name] Shaded

[colour-name] Smoke

[colour-name] Silver Tabby

[colour-name] Silver Tabby-Tortoiseshell ([colour-name] Silver Patched Tabby)

[colour-name] Silver Ticked Tabby, [colour-name] Silver Abyssinian/Somali

Some of these colours have probably turned up historically, but have not been recognised as distinct colours. For example, some early tipped, shaded and smoke cats were described as poorly coloured. "Poorly coloured" Blue Smokes were very likely Lilac Smokes, a colour not recognised or understood at the time.

The Golden series is also relatively recent and is still uncommon:-

Golden Chinchilla, [colour-name] Golden Chinchilla

Shaded Golden, [colour-name] Shaded Golden

Golden Smoke, [colour-name] Golden Smoke

Golden Tabby

Golden Tabby-Tortoiseshell (Golden Patched Tabby)

Golden Ticked Tabby, [colour-name] Golden Ticked Tabby

Golden tabbies are derived from Chinchilla/Shaded Silver cats. Because the Inhibitor gene is dominant, a shaded/tipped cat might carry a hidden recessive form of that gene. If two recessive carriers are bred together, there is a good chance that some kittens will inherit two copies of the recessive gene, giving rise to a Golden. They cats are different from other tabbies, being brighter in colour due to wider colour bands on the hair shaft.

SMOKE

Smoke is caused by the combination of the dominant Inhibitor gene with the recessive Non-agouti gene. The Inhibitor gene gives rise to a pale undercolour. The extent of this undercolour is variable and the smoke can be described as light, medium or dark depending on the amount of top-colour (tipping, known as "veiling" in smokes) and the extent of the pale undercolour i.e. how far the pale colour extends along the hair shaft. Occasionally a Smoke can be so light in colour that on visual inspection it is Shaded cat (e.g. a very light Black Smoke resembling a Shaded Silver), although true Shaded cats have the Agouti gene, not the Non-agouti gene.

In smoke cats, the undercolour varies from almost white to a bluish grey. Cats with darker undercolours may look self coloured, especially in black cats. It is possible to have a cat which is genetically a smoke, but which is visually solid black! The heavy tipping combines with a very narrow white hair base so that the smoke effect is lost. This variation in the relative amounts of undercolour and top-colour appears to be due to modifier genes and mirrors the way in which modifier genes act on shaded silvers to produce both shaded cats and chinchillas (and often in the same litter). Some smokes, known as overlaps, never develop the silvery undercoat and only prove to be genetically smokes when bred.

Smoke kittens sometimes show faint tabby markings (as seen in the photo on this page). Young smoke Persians look almost solid in colour except for a silver tracery (clown lines) where the agouti areas would appear in a tabby. Not all kittens have clearly visible clown lines, but those that do have them tend to develop more striking adult coats. In adults, the presence of clown lines is penalised. The smoke effect is more obvious in longhaired cats and is not restricted to black smokes. Other colours can be combined with the Inhibitor gene to produce blue smokes (black + dilute modifier + Inhibitor gene), chocolate smokes, lilac smokes and red smokes. Black, blue and red are the longest established and best known varieties. Some of the "newer" colours have appeared historically and were probably dismissed as "poorly marked" individuals in one of the then known colours.

The Red (Cameo) Smoke is produced by a combination of the Inhibitor gene and the gene for red. These have a red/orange tipping on a whitish undercolour. Because of the way in which red colour is inherited (Tortoiseshell and Tricolour Cats), the males are red, but the females may be either red or tortoiseshell.

The Non-agouti gene has no effect on the red colour as it is produced by a different pigment. This means that the difference in appearance between Red Smokes and Red Shaded Silvers/Red Chinchillas is not due to the cats having the Agouti or Non-Agouti gene as it is with the other colours. The Agouti gene affects non-red colours such as black, blue, chocolate etc so it does make a difference in whether the non-red areas of tortoiseshells turn out as smoke (Non-agouti) or as silver tabby, blue silver tabby etc (Agouti).

The difference between Red Smoke, Red Shaded Silver and Red Chinchilla appears to be due to the Inhibitor gene causing the pale undercolour and various modifiers dictating how far along the hair shaft the undercolour and top-colour extend respectively.

The Cream Smoke, Cream Shaded Silver and Cream Chinchilla are due to the presence of the dilution gene in addition to the red gene. In the tortoiseshells, this additionally turns a red/black tortoiseshell into a blue smoke tortie or a blue silver tabby tortie.

Shorthaired solid colour cats tend to have have ghost tabby markings which are particularly visible in kittens. As a result of ghost markings, Smoke shorthairs may appear to be Smoke tabbies. Hence the Black Smoke Egyptian Mau has visible spots on a Smoke background. According to Phyllis Lauder's book "The British, European and American Shorthair Cat" (1981), the Smoke factor can turn up in unexpected places. Lauder had a Blue Cornish Rex with underfur of the ash-white colour proper to a Smoke. When the cat was 2 years old, she noticed that the fur behind his ears looked silver. At the time, he could not be described as Smoke according to the standards for that colour (which demanded a light silver fril; and ear tufts and an ash-white undercoat tipped with blue), but he was nevertheless a Blue Smoke. The appearance of the smoke factor was not always welcomed by breeders. In particular, there were complaints that Red and Cream longhairs showed an undesirable degree of white in the undercoat.

SILVER TABBY

Silver tabby is also caused by the dominant Inhibitor gene, but this time in combination with the dominant Agouti gene. Silver tabbies have a silvery background colour with a tabby pattern overlaid on it. Silver tabbies in the random breeding population are prone to tarnishing - the appearance of a yellowish or rusty hue. The Inhibitor gene seems eliminate the yellow pigment in the agouti (ticked) hairs of the background colour, but does not affect the non-agouti areas (the markings). In longhairs, the silver pattern is diffused by the hair length although residual striping may be seen on the legs and face.

The growing popularity of the Chinchilla Persian was at the expense of the silver tabbies which almost vanished (although World War 2 also caused many breeds to go into serious decline). In 1951, Soderberg wrote "Silvers - this breed has almost disappeared, and at the present time there are only very few breeders who are attempting to bring it back to the popularity which it possessed at the beginning of the century. Admittedly it is a difficult breed, and the only specimens which one now sees are lacking in type. A really good specimen could expect to win premier honours at a show, and it is well worth attempting to produce such a "flyer". Although the Silver Tabby is definitely one of the neglected breeds, it would be a thousand pities if it were allowed to sink into oblivion."

|

Silver Mackerel Tabby

|

Silver Classic Tabby

|

The best known silver tabbies are the shorthaired black versions (widely used in advertising), simply called Silver tabbies. These have black markings on a silver undercoat (as shown in the photo; this cat has some tarnishing). Other silver tabbies are prefixed by the name of the marking colour e.g. Blue Silver Tabby, Chocolate Silver Tabby, Lilac Silver Tabby, Cinnamon Silver tabby and Fawn Silver Tabby. Pewter Tabbies are now more correctly known as Blue Silver Tabbies.

There are also Red Silver Tabbies (Cameo Tabbies) and Cream Silver Tabbies (Cream Cameo Tabbies) which have red markings and cream markings respectively on a silvery background.

The Inhibitor gene has also been introduced into Abyssinians and Somalis to create silver-undercoated varieties of ticked tabby. These are popular in Britain, but less well known in the USA. The Alaskan Snow Cat has the silver ticked tabby pattern, but has a more rounded shape.

The Silver Tabby has an identical genetic make-up to the Shaded Silver and Chinchilla. The amount of pigmentation depends on minor sets of genes (polygenes).

SHADED SILVER AND CHINCHILLA (TIPPED)

Shaded Silver and Chinchilla are also caused by the dominant Inhibitor gene in combination with the dominant Agouti gene. The underlying tabby pattern is demonstrated by chinchilla kittens which appear silver tabby until the hair grows long enough for the white undercolour to be properly developed. As the hairs become longer, the tabby pattern is diffused and only the very tips of the hair are coloured, producing a sparkling effect. Occasionally a Smoke (Non-agouti) can be so light in colour that on visual inspection it is Shaded cat (e.g. a very light Black Smoke resembling a Shaded Silver); however it is different genetically.

The first silver chinchillas were developed from unsound or spoiled silver tabbies mated to lightly tipped smokes. Unsound or spoiled silver tabbies were those where the silver undercoat was evident at the base of the black hairs which formed the markings. Because chinchillas resulted from crossings to smokes, it was thought that a single factor (what would now be called a gene) was responsible for chinchillas, shaded silvers and smokes. There are light, medium and dark smokes and light smokes were sometimes mistaken for shaded cats and bred with chinchillas.

Selective breeding has increased the amount of undercolour and reduced the extent of top-colour. The long fur emphasises the undercolour and prevents the hair tips from forming a recognisable tabby pattern. Some tabby effects may still be seen in body areas with shorter fur: the face and lower legs. The longer the fur, the better the pattern is dissipated, hence shaded shorthairs are at a disadvantage compared to the longhairs. Although some Shaded shorthaired cats have a tabby pattern at birth, this should be dissipated by hair length in adulthood. Sometimes the tabby pattern persists into later life and is considered a serious fault (or the cat is quietly reclassified as a tabby). There are likely to be various modifier genes which further disperse the tabby pattern and reduce the pigmentation of the hair shaft by creating wider bands.

The Shaded Silver and the Silver Chinchilla (usually known simply as Chinchilla with no colour qualifier) are the most familiar of these cats and the longest established. They are not the only colour variants though. The Blue Chinchilla is the dilute form of the Chinchilla and appears almost identical. Blue Chinchillas are most easily distinguished as kittens when the blue colour is less diffuse.

The Chocolate Chinchilla is also most easily identified in kittenhood. Adult Chocolate Chinchillas have dusky-brown or "off-black" tipping. Lilac Chinchillas, Cinnamon Chinchillas and Fawn Chinchillas are also possible.

The Red Shaded Silver and Red Chinchilla (and also Tortoiseshell Shaded and Tortoiseshell Chinchilla) are produced by a combination of the Inhibitor gene and the gene for red. The difference in appearance between the Red Shaded Silver and Red Chinchilla is due to modifiers acting on the extent of the undercolour and top-colour along the hair shaft. The Agouti gene affects non-red colours such as black, blue, chocolate etc so it does make a difference in whether the non-red areas of tortoiseshells turn out as shaded/tipped (Non-agouti) or as silver tabby, blue silver tabby etc (Agouti).

The Cream Shaded Silver and Cream Chinchilla are due to the presence of the dilution gene in addition to the red gene. In the tortoiseshells, this additionally turns a red/black tortoiseshell into a blue smoke tortie or a blue silver tabby tortie.

In 1969 or the early 1970s, Mrs Worthy of Hertfordshire bred some unusual Devon Rex twins whose white coats were “sprinkled exotically with lilac highlights”. The only photo is a black and white one, showing the cats as having darker noses (not surprising, since the hair is shortest on the nose). These would seem to be lilac tipped, though by all accounts they were somewhat unexpected!

The Chinchilla's sparkling looks mean it is often associated with luxury, quality and class; Chinchillas are therefore used in advertising products which want to appear a cut above the rest.

PEWTER

During the course of breeding Shaded Silvers and Chinchillas, what looked to be orange-eyed Shaded Silvers appeared. These were known as Pewters or Pewter Tipped. Some of the earliest Pewters may have been genetically blue (grey) rather than black or may have been light Smokes. Still not common compared to Chinchillas and Shaded Silvers, the modern Pewter has heavier tipping than the Shaded Silver resulting in a darker mantle.

The first Pewters were bred sometime in the 1970s and found in the "Any Other Colour" classes along with other Shaded cats of then unrecognised colours (some of those cats are now recognised as Chocolate Shaded and Lilac Shaded). The Black Pewter gained Championship Status in 1986 in the UK. Still considered by some to be a poor relation of the Shaded Silver, the Pewter remains comparatively rare.

In the late 1890s and early part of the next century, orange eyes were standard for Chinchilla and Shaded Silver cats. Green eyes, now a prominent feature of these cats, were actually considered a fault in those days! Those with a sense of history are pleased to see the ancestral eye-colour being bred again and Blue Pewters have also been recognised.

The term Pewter Tabby has been used historically to describe the Blue Silver Tabby.

MASKED SILVER

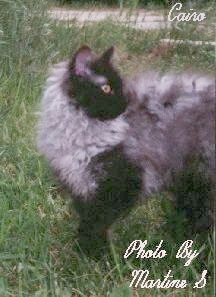

Resembling the Shaded Silver in all respects apart from dark mask and dark legs, the Masked Silver is believed to be a "light" Black Smoke i.e. a Non-Agouti cat with the Inhibitor gene. On the body, the top-colour is reduced to no more than half the length of the hair producing the visual effect of a Shaded Silver. On the face and legs, however, the top-colour extends further along the hair shaft, indicating the cat's true type. It is more apparent in modern Shaded shorthairs although some very attracted Masked Silver Persians have been bred in the past.

Martine Sansoucy of Butterpaws LaPerms has seen a number of masked silvers and notes that they appear to be smokes rather than shaded silvers. Butterpaws BC The Crow, known as "Cairo" is a black smoke that meets the general description of a masked silver. As can be seen from the photo, the different textures of fur on the face and the body give the impression of a masked cat with the black colour being more intense on the straighter fur.

|

Historical Masked Silver.

|

Masked Silver (black smoke) LaPerm.

|

Some authors have written that the masked silver dates back to 1900, but were probably referring to the shaded silver, a variety not recognised in Britain at the time and considered to be a badly bred chinchilla. According to Milo Denlinger in 1947, "Masked silvers are a new variety and very few are bred." Denlinger went on to describe the variety: "The ideal masked silver is a very beautiful animal; in colouring or, I should say, marking, they should resemble the Siamese Cat; that is to say, they should have a black mask, or face, black feet, and legs. The body should be as pale a silver as posible." The eyes were to be deep golden or copper. Several authors have observed that the description of the masked silver resembles that of the Siamese. The Masked Silver was also described by Mery and others in the 1960s.

Before the Shaded and Smoke cats patterns were known to be genetically distinct, this was regarded as a sub-type of Shaded Silver and a number of attractive Masked Silver Persians were bred. Some were described as having darker bodies (mantles) than Shaded Silvers".

|