EARLY GOLDEN CATS - SABLES

Mirroring the silver series, there is the newer and less common golden series. One of the most famous early chinchillas was called Silver Lambkin, and it seems likely from descriptions at the time that he gave rise to both silver and golden kittens. Unknown to early breeders who did not have the benefit of genetics knowledge, where there are Chinchilla Persians, Silver Tabby Persians and Silver Tabby Shorthairs there would usually be Golden and Golden Tabby cats too. These were generally considered , known as "brownies" and discarded, though some Golden Tabbies no doubt found their way into the Brown Tabby Class since early writers differentiated between the "Brown Tabby" and the "Sable Tabby".

The GCCF studbook of 1925 listed a "sable chinchilla" male called Bracken, whose parents were Caiville (male) and Minetta (female). Bracken appears to have been an early Golden Persian and apparently had a chinchilla female littermate. An influential "silver" (Chinchilla) female, Recompense of Allington, was born from another mating of Caiville to Minetta and there is a 75% probability that Recompense carried the Golden gene which popped up in Chinchilla descendants later on. Evelyn Buckworth-Herne-Soam's 1933 book included a chapter on the Brown Tabby Longhair. She commented on the very successful Brown Tabby Longhair of 1896, Champion Birkdale Ruffle and also on a much later "rich sable colour" cat called Treylstan Garnet and referred to the colour class as "brownies", then the term for the brown tabby (as opposed to "silvers").

In 1927, Mrs Sydney Evans placed her Longhair Sable at stud. The cat was acquired from Mrs Jourdain who knew of several cats of that variety and hoped that they might become better established. All were bred from Chinchilla stock. Sable was excellent in type and had a good sable coat with black tips (called ticking, but not to be confused with the Abyssinian) along the spine and on the tail, head and paws. His eyes were emerald green.

Assuming that the "Sable Tabbies" of history were in fact Golden Tabbies, the following descriptions of Sables from around 1903 give an insight into the early history of the golden series.

The 1903 "Book of the Cat" stated: "There is a distinct kind of brown tabby, which may better be described as sable. These cats have not the regular tabby markings, but the two colours are blended one with another, the lighter sable tone predominating. At the Crystal Palace Cat Show of 1902 the class was for brown tabby or sable. I was judging, and, considering the mixed entries, I felt that markings must not be of the first importance, and so awarded first and second to Miss Whitney's beautiful sable females, the third going to a well-marked though out of condition brown tabby. ... These sable marked cats are rare, but still more beautiful would be a cat entirely of the one tawny colour - a self sable, without markings. "The most suitable factors to obtain this colour," so writes Mrs Balding, "would probably be tortoiseshell-and-sable tabby, as free from marking and as red in ground colour as possible. A cross of orange, bright coloured and as nearly as obtainable from unmarked ancestors, would be useful. Some nine years ago I purchased a dimly marked bright sable coloured cat, 'Molly,' shown by Mrs Davies at the Crystal Palace, with a view to producing a self-coloured sable cat; but 'Molly' unfortunately died, and I abandoned the ide The nearest approach to a self-sable I have ever come across was a cat I obtained for the Viscountess Esher, which had, alas! been neutered. He was almost unmarked, and of the colour of Canadian sable, with golden eyes - a most uncommon specimen."

Frances Simpson wrote: "For sables we, of course, go to the Birkdale strain. I remember the incomparable "Birkdale Ruffie" in his full glory at the Crystal Palace - a mass of red-brown fur, of the style of "Persimmon Laddie," but with more distinct markings and a very keen, almost fierce expression; in fact, he looked like a wild animal! Then "Master Ruffie" appeared as a kitten, and later as a mild edition of his sire. From this celebrated strain Miss Whitney's lovely sables are descended. ... the brown tabby and sable, though often classed together, must not be confounded. The brown tabby is supposed to be the common ancestor of all our cats, and hence the tendency to revert to that colour. ... They appear in very unexpected places - in a litter of chinchillas or blacks, or among our oranges, and sometimes where no brown ancestor can be traced. ... As regards the sables, I may remark that they are late in maturing and do not acquire their marvellous colouring till about the second year ." (She also remarked that sable tortoiseshells existed)

Miss Southam described Birkdale Ruffie in Frances Simpson's The Book of the Cat: It was at the West of England Cat Show in 1894 that 'Birkdale Ruffie' scored his first real success winning two first prizes in the open and novice classes and two specials. Here at last his beautiful sable colouring, his dense black markings, and wonderful expressive face were appreciated. The year 1896 was the occasion of his sensational win at the Crystal Palace show. He simply swept the board, carrying everything before him - first prize, championship, several specials, and the special given by the King (then Prince of Wales) - for the best rough-coated cat in the show. Again, in 1897, he was shown with great success at the Crystal Palace, winning first prize, championship and special. This was the occasion of 'Birkdale Ruffie's' last appearance before the public, as it was during the following month my sister was taken dangerously ill, and for this reason his pen at the Brighton show was empty. After her death we determined to subject him no more to the trials and discomforts of the show pen so 'Ruffie,' who was now seven years old and a great pet, both for his own sake and that of his mistress, only too gladly retired […] watching his facsimile, his little son 'master Ruffie,' growing up more beautiful each day and ready to take up the thread of his father's famous career in the exhibition world.

Into the latter 'Master Ruffie' made his debut without any of the numerous anxieties encountered by his celebrated parent. The way was paved for him, and when he appeared at the Crystal Palace show in 1899, in all the full glory of his youth and beauty, it was difficult for the judges to realise that it was not their old favourite who was now confronting them through the wires. 'Master Ruffie' has only been shown on two occasions - in 1897 as a kitten, and in 1899 at the Crystal Palace, when he returned home with his box literally filled with cards, his winnings including three first prizes, four specials, and a championship. I am sorry we can manage to get no really good photo of 'Master Ruffie' … steadfastly refuses the face the camera. Again and again the button is pressed in vain, and only the glimpse of a vanishing tail upon the negative is all we have to show as 'Ruffie's' portrait! [Master Ruffie] is a very cobby little fellow, being perhaps shorter in the legs, which makes him appear to be a somewhat smaller cat than his father. 'Birkdale Ruffie' was noted for the extreme beauty of his expression; he had certainly one of the most characteristic faces ever seen in a cat, and his son inherits the same. The former was constantly the subject of sketches in the illustrated papers, those by Mr Louis Wain being especially lifelike. Some of 'master Ruffie's' descendants are, I believe, in the possession of Miss Witney, and have met with great success in the show pen."

Miss Witney wrote "'Brayfort Fina' is, I may say, a sable tabby, being particularly rich in colour all throughout - indeed, more often of an auburn tan than brown. ...'Fina' was bred by Miss G Southam, and is by 'Master Ruffie' ex 'Bluette,' her sire being a son of the famous 'Champion Birkdale Ruffie.' [In 1902 'Fina' took first] at the Bath Specialist Show in the same year, where her gorgeous colouring was called in question and an unsupported protest was made that she was dyed!

THE GOLDEN SERIES

Until relatively recently some breeders believed goldens to be the result of more recent mis-matings between chinchillas and self Persians. At present the genetics of the golden series are not fully understood. The naming convention is below. Being a newer variety, the naming convention is standardised hence [colour-name] indicates the tipping/shading colour e.g. Blue Shaded Golden, Tortoiseshell Golden Chinchilla. Where a cat is described with no addition "colour-name" the tipping/shading/tabby etc is assumed to be black. The Golden Tabby is equivalent to the Silver Tabby with distinct markings on a golden background.

Golden Chinchilla, [colour-name] Golden Chinchilla

Shaded Golden, [colour-name] Shaded Golden

Golden Smoke, [colour-name] Golden Smoke

Golden Tabby

Golden Tabby-Tortoiseshell (Golden Patched Tabby)

Golden Ticked Tabby, [colour-name] Golden Ticked Tabby

Golden tabbies are derived from Chinchilla/Shaded Silver cats. Because the Inhibitor gene is dominant, it is believed that a shaded/tipped cat might carry a hidden recessive form of that gene. If two recessive carriers are bred together, there is a good chance that some kittens will inherit two copies of the recessive gene and this was believed to be the cause of golden chinchillas, shaded goldens and golden smokes. This theory is shown below; the "silver agouti" means a tipped or shaded cat.

|

|

I (Inhibitor)

|

i (non inhibitor)

|

|

I (Inhibitor)

|

II

(Silver homozygous)

|

Ii

(Silver heterozygous)

|

|

i (non inhibitor)

|

Ii

(Silver heterozygous)

|

ii

(Non-silver i.e. golden)

|

Non-silver cats with the agouti gene are known as Golden Tabbies, Chinchilla Golden or Shaded Golden depending on whether they have the tabby pattern, shaded pattern or chinchilla tipping. These cats are different from other tabbies. They are much brighter in colour due to wider colour bands on the hair shaft. The hairs are almost wholly golden with a darker tip and a pale or greyish undercolour near the base of the hair.

The variability of chinchilla and shaded cats, and the existence of golden series cats, has led breeders to hypothesise the existence of a separately inherited recessive "Wide Band" gene that would brighten brown tabbies to golden tabbies and brighten shaded cats to chinchillas (tipped cats). This affects the banding pattern of individual hairs, producing a wider-than-normal band of bright colour. Wide Band would determine the width of the hair shaft colour (the undercoat) between the pigmented tip and the follicle. The presence or absence of the Inhibitor gene does not affect Wide Band since Golden Shadeds lack the Inhibitor gene, but have a shading pattern comparable to Silver Shaded cats. According to this theory, golden series cats would not be golden due to a recessive form of the inhibitor gene, they would be golden due to the separately inherited wide band gene.

Still others consider it more likely that the colour is caused by multiple interacting genes (polygenes) producing a combined effects.

These photos from Lisa Wahl (www.blindcougar.org) show golden tabbies. Some have red markings and others have brown markings, but the background colour is bright golden. The cats came from a breeder who had died, leaving behind a line of golden "Maine Coon type" cats she had developed from barn cats, plus extensive breeding records. Some of the 50 cats rescued have very red undersides, and black paw pads.

LATE COLOUR CHANGE "GOLDENS" & THE BLACK MODIFIER GENE

Over the years, there have been accounts of pure silver Persian kittens turning to a pale golden colour as they mature. This often began with yellowish "tarnish" or cream spotting appearing in the coat of a shaded silver or chinchilla cat. Reddish hairs first appeared on the spine, face or paws, and progressed through a yellowing of the undercoat. Chinchillas derived from chinchilla-to-chinchilla matings sometimes exhibited reddish or golden hair along their spines which was attributed to incomplete dominance of the golden gene "breaking through" in the coat. Some silver kittens were, when 2 or 3 years old, very definitely pale golden adults. Offspring born to such cats were born as silvers, showing the "golden" cat was genetically a silver, but some of those offspring also had a tendency to turn golden at about 2 or 3 years old.

Silver and chinchilla cats have been selectively bred to eliminate (as far as possible) polygenes that would modify the colour's purity. The silver should, therefore, be devoid of genes that cause cream, yellow and red pigment. Yellow denotes the technical term for the pigment granule which produces all of these colors. Polygenic complexes have plus and minus polygenes that influence the trait. Diligent breeding resulted in accumulations of either plus or minus polygenes in a specific breed or colour. However, these polygenes are carried on different chromosomes and inherited independently of each other.

In silvers, the inhibitor gene means the round granules of eumelanin (black) are absent from most of the hair shaft and are clumped near the tip. Being incompletely dominant, the effect ranges from shaded silver through to tipped (chinchilla). In normal goldens, the granules of the yellow pigment phaeomelanin are likewise influenced by the inhibitor gene. However, the silvers that turn into goldens don't have any phaeomelanin. Instead, these "pseudo-goldens" turned out to have an additional mutation that caused their eumelanin granules to be elliptical rather than round and to show as a beige or pale golden colour. These mutant granules are not completely eliminated from the hair shaft, but are smeared along it, causing a pale golden undercoat. They are also clumped at the tip to give the shaded or tipped effect.

Eumelanin is usually described as "black", but is actually a deep brown (sepia) that appears black to our eyes. As the eumelanin granule becomes elongated, it appears paler and more reddish-brown or dark-yellowish-brown. The concentration of the mutant eumelanin granule on the hair shaft gives colours ranging from copper-brown through apricot to reddish honey, all with darker tips. The mutated eumelanin gene has been described as a "late colour change" gene for obvious reasons. Its mode of inheritance not fully understood. It is also possible that some apparently golden-from-birth Persians may be pseudo-goldens and can have silver kittens - generally considered an impossibility as silver is dominant over normal golden and cannot be carried as a recessive (though silver can reoccur as a spontaneous mutation).

A "late colour change" mutation, again causing an end result of golden, has been observed in Norwegian Forest Cats. The Black Modifier gene, found in Norwegian Forest Cats, brightens black or blue areas of the coat to Amber (apricot-to-cinnamon colour) and Light Amber (pale beige). At birth, kittens appeared to be black or blue, and lightened to Amber or Light Amber respectively. Amber has also occurred in conjunction with silver: the kittens were born as poorly coloured black-silver or blue-silver tabbies whose tabby ghost-markings faded as they matured and their colour became a bright apricot to cinnamon colour with dark brown paw pads and nose leather with no black rim (the black rim is characteristic of silvers). Their original birth colour could be seen only on the back and tail.

This Norwegian Forest Cat was bred by Yve Hamilton Bruce from a silver mackerel tabby female (imported from Denmark) and a classic red tabby and white male. The result was 1 silver tabbies and 2 silver tabbies with white. At just over 3 months old, this silver and white tabby male developed a large patch of bright red hair on his back. Eventually the whole fur will become amber. The effect of amber during the colour-change stage depends on the original colour - solid black or blue, bicolour or tabby.

MORE-THAN-TIPPED BUT NOT-QUITE-SHADED CATS

The criteria for each degree of tipping is an ideal and there are many cats which visually fall between two ideals.

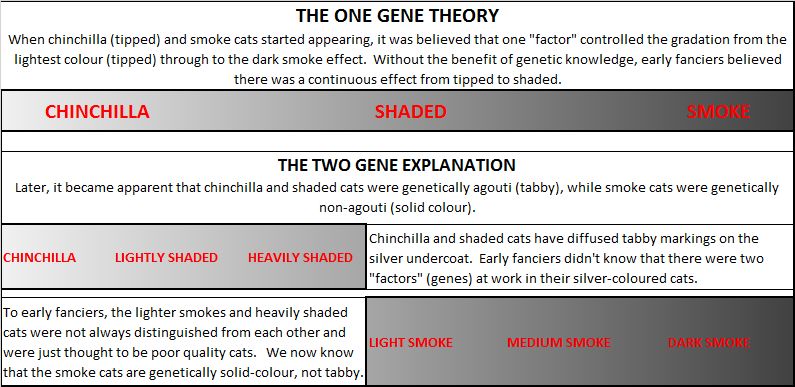

Although the genetic combinations are different; smoke = Inhibitor + Non-agouti while shaded/tipped = Inhibitor + Agouti, the variability of expression results in cats which seem intermediate in colour. This is a "two gene theory" where the two genes involved are the Inhibitor and the Agouti/Non-agouti genes. There are pet quality cats where the tipping is too heavy for it to be a well marked chinchilla, but too light for it to be a shaded silver. There are also shaded silvers dark enough to resemble the genetically different "light" black smoke. These differences are caused by various polygenes. This "two gene" theory is the one to be found in modern feline genetics texts. Before this interaction was understood, there was believed to be a recessive "chinchilla gene" which controlled the degree of tipping.

Before the genetics of these cats was well understood, the apparent continuous gradation between chinchilla through to smoke would have resulted in some matings between mis-identified cats. For some while, it was believed that Smoke, Shaded and Tipped were all variable effects of the same gene (or "factor" since the term "gene" was not in usage in the early days of cat breeding). This "one gene theory" seemed to be borne out by the fact that some Shaded cats were so dark as to be poorly marked Smokes, while Smokes occurred in a range of intensities from light (Masked Silver) through to dark (solid colour). And of course, the earliest shaded and chinchilla cats were seen to have come from mating tabbies with smokes.

In Tipped/Chinchilla and Shaded kittens, the tabby pattern may still be visible as it is the long hair which diffuses the colour. In Smoke shorthair cats, just as in many solid black cats, a tabby pattern is often still discernible in the form of ghost markings. This pet kitten appears to be a black smoke tabby and white (or a heavily marked shaded silver with white). In adulthood, the tabby markings will be obscured by his long fur. Smoke-and-white and Shaded-and-white are not colour varieties accepted by registries.

Those cats which meet neither the Chinchilla/Tipped nor the Shaded standard are still attractive pets.

GENETIC THEORIES FOR SHADED CATS AND SILVER TABBIES

The earliest theory suggested a Chinchilla gene which was a version of albino. Work by Keeler and Cobb seemed to indicate that the gene producing "silver" or "smoke" in cats was an allele of the same gene that produced the Siamese coat pattern i.e. a form of albinism. They described the effect of silver as and producing the following types of hair (1) all white, (2) all black (in dark silvers or smokes), (3) black hairs with white tips, (4) hairs with white and grey or black bands, and (5) white hairs with black tips. However, this would rule out the possibility of Shaded Sepia, Shaded Mink and Shaded Pointed colours. Since these colours have been shown to be possible in experimental breeding (even if not present on the showbench), the Chinchilla gene theory was obviously incorrect.

A second theory proposed a single dominant Inhibitor gene, but this could not explain the variations of shading. In addition, breeding demonstrated that Smoke cats were genetically different from Shaded and Chinchilla (Tipped) cats and not variable expression of a single gene.

The current theory, and even this may ultimately be disproved, is that there are at least two genes involved and that these interact to produce different effects. There are also a number of as yet unidentified polygenes which may influence the colour and pattern.

Originally, the Inhibitor gene was thought to work similarly to White. In white cats, either the melanocytes (pigment-forming cells) are absent or abnormalities in the cells means that pigment can't be produced. The Inhibitor gene does not work this way.

In silver tabbies, the pigment cells produce far less pigment than normal. Pigment is laid down at the hair tip, but little is laid down on the hair shaft which appears silver or grey rather. If pigment was entirely absent, the hair shaft would be pure white. Sometimes the Inhibitor gene fails to completely block phaeomelanin (the red pigment) and the resulting breakthrough of reddish colour is known as "tarnishing". Tarnishing can often be seen on the muzzles of random bred silver tabbies, but rarely on pedigree silver tabbies (a refinement which sets the purebred version apart from the random-bred version).

In Non-agouti (non-tabby i.e. solid colour) cats, the Inhibitor gene only lightens the undercoat area. Where it fails to completely block residual pigment production, the undercolour is grey rather than white.

WIDE BAND

In addition to the Inhibitor gene (not present in the Golden series), a silver cat may also have the Wide Band gene The existence of a "Wide Band" gene is disputed. If it exists, Wide Band determines the width of the hair shaft colour (the undercoat) between the pigmented tip and the follicle. The undercoat length varies, being narrow on the cat's back and wider at the belly. It is believed that the presence or absence of the Inhibitor gene does not affect Wide Band since Golden Shadeds lack the Inhibitor gene, but have a shading pattern comparable to Silver Shaded cats. There may be polygenes which affect the undercoat width rather than a single Wideband gene; some ideas are mentioned in the section below.

Wide band is considered as either an effect (due to interacting genes) or as a gene. Leaving the exact mechanism aside, it can be treated as a dominant gene when looking at inheritance. If a non-agouti cat (self/solid cat) has dominant wide band (Wb), this will not show up unless it also has silver in which case it is a smoke. In tabbies, Wb may account for the different appearance of silver tabbies, shaded silvers and chinchillas (tipped). If a non-agouti cat has silver but has recessive wide-band (wb or narrow-band), it could account for the poor smokes and hidden smokes. Wide-band is noted to have an additive effect - one copy is wide band, 2 copies is even wider band. There may even be multiple alleles of wide-band.

While the Agouti gene permits the hairs to have bands of colour, separate genes for banding frequency, band width and band placement probably influence the banding pattern of the hairs. An ideal Shaded Silver hair would have a single broad band of pigment at the tip of each hair. Shaded Silvers have a mix of three patterns: a single broad band and wide undercoat; a few broad bands and wide undercoat or multiple thin bands (as seen in the background colour of Silver Tabbies).

Burmilla breeders who rarely saw tipped cats in early generations, but saw them frequently in later generations, even suggest that in addition to dominant wide-band there may be a second recessive "super wide band" gene for tipping. However these effects are equally attributable to inheriting either one or two copies Wb.

In goldens, wide band refers to the yellow banding of the hair shaft. Wide-band would have no effect on a non-agouti cat as the hair shafts are not banded. A eumelanin series cat (black/brown) can have the recessive form of inhibitor gene (golden), but doesn't have true red pigment (phaeomelanin), so the undercoat is warm cream or apricot rather than bright golden. For that reason, it's suggested that some poor quality silvers are really creamy goldens that give the illusion of having silver.

EFFECT OF OTHER GENES

There are probably other genes that influence the number and width of coloured bands on each hair and reduce or eliminate residual tabby markings on the chest, legs and sometimes tail. Yet other genes probably influence the sparkling appearance. In addition to the Agouti gene and Inhibitor (silver) gene, a Shaded cat may also have the Wideband gene (hypothetical) plus genes which influence the number and width of coloured bands on each hair and reduce or eliminate residual tabby markings on the chest, legs and sometimes tail. Yet other genes probably influence the sparkling appearance.

Some tipped and shaded silver shorthairs may have the ticked (Abyssinian-type) tabby gene in addition to the classic or mackerel tabby gene(s). This only shows up if matings of Shaded Silvers to Classic Tabbies unexpectedly produce ticked tabby kittens. Since ticked tabby masks out any other tabby pattern, it could only have been carried by the Shaded Silver parent. Tipped or Shaded Silver kittens born without a tabby pattern probably carry the ticked tabby gene, while those born with a discernible tabby pattern may lack the ticked tabby gene.

Breeder of Shaded Silver American Shorthairs, Carol W Johnson, suggested at least two modifier genes which affect ticked tabbies and which dissipate residual tabby markings in shaded shorthairs. She referred to them as Chaos and Confusion. A third gene. "Erase" was proposed by Cathy Galfo (working with Oriental Shorthairs) and appears to reduce or remove residual barring on the extremities. Currently, these names describe effects rather than actual genes.

Johnson noted that the each hair in a shaded cat differs in band number and width; ranging from solid colour and solid white through to multiply banded and singly banded. She termed this "Confusion" as it "unco-ordinated" the hair follicles to so that they produced different banding patterns to their neighbours. In contrast, Abyssinian-type ticked tabbies have even banding and relatively even colouration which stops abruptly at the belly (like a tide mark on a boat!). Shaded cats with high levels of Confusion (uneven band width) had a more mottled or "sparkling" appearance and a more gradual blending and fading of the colour from back to belly.

However, the confusion effect can be achieved with polygenes. Except for genes on X and Y chromosomes, each cell has 2 copies of each gene. The 2 copies might be identical or different and normally one is dominant to the other. Sometimes, e.g. when the genes are different but co-dominant, one copy is deactivated; this happens in foetal development. One cell might have activated the gene telling it to make 3 bands of colour while the cell next to it might have activated the slightly different copy of the same gene telling it to make 5 bands of colour. There might be a gene located elsewhere on the chromosome which, if switched on, override those genes entirely with an instruction to make a solid coloured hair! So while "Confusion" is a good name for the phenomenon on a visual level, a single Confusion gene seems unlikely.

In addition to Confusion, Johnson also hypothesised a rarer gene causing roan. In roan, solid white hairs are intermixed with normal hairs. This occurs in dogs (merle, roan) and horses (roan, flea-bitten grey). In Shaded shorthairs, "Roan" might result in Shaded Silvers so pale as be visually Chinchillas.

Johnson's "Chaos" gene further disrupts the striped pattern by abnormally mixing ticked hairs into normally solid coloured regions (and vice versa). This effect is visible in the modified tabby pattern of the Sokoke. An mechanism for this was described by Australian Mist breeder Truda Straede who suggested a gene which disrupted a normal tabby pattern into a "finely divided tabby pattern" (Striped and Spotted Cats). Straede had never seen the Sokoke, but predicted the patterns existence based on her work with "small pattern spotted tabbies" and "large pattern spotted tabbies". Chaos might eradicate residual necklaces and ghost striping in ticked tabbies and in Shaded cats.

Cathy Galfro proposed a separately inherited "Erase" gene, different to Confusion and Chaos, which removes residual markings from the neck, legs and tail of Shaded Oriental Shorthairs.

RECESSIVE SILVER

As detailed above, silver (the inhibitor gene) is dominant while the recessive (hidden) version is golden. If a cat is not silver, genetically it must be golden. The phenomenon of a non-silver cat producing silver offspring when bred to an apparently non-silver cat has been documented several times. For example, Neils C Pedersen, Feline Husbandry, 1991 (pg 67) reported "several cases on record of black cats breeding as smokes." Robinson’s Genetics for cat Breeders and Veterinarians, 4th Edition, 1999 (pg 142) reported "occasional cats with no visible white undercoats that nonetheless breed as smokes.” Gloria Stephens’ Legacy of the Cat, 1989 & 1999 admitted "we do not understand about silver or the gene(s) that cause a solid-colored cat to be smoked.” The variability of smoke cats, ranging from poor smokes and hidden smokes to light smokes, is mentioned as far back as Frances Simpson in the early 1900s (this book pre-dates modern inheritance genetics so you have to rely on descriptions, some of her light smokes are evidently smokes). Some apparently solid cats are genetically smoke, but other genes prevent the pale undercoat showing up. However, could there be another form of silver, one that is either hypostatic (masked fully or partially by other colour genes) or is a second recessive allele of the inhibitor gene I and is recessive to both I (silver) and i (golden), but which produces a form of silver, perhaps i2 where dominance is I > i > i2.

All non-silver cats are, by default, by golden, though the golden will not show up in solid (non-agouti) cats. However, unexpected silver cats has turned up from time to time when two non-silver cats (by default golden) have produced silver offspring or a non-silver (golden) mated to a heterozygous silver (silver carrying golden) have consistently produced silver kittens, but non goldens even though the law of averages would expect half of the offspring to be non-silver.

What are the possibilities?

-

Mutation of the gene into the dominant inhibitor (silver) is plausible if it happened in the germ cells (ova, sperm) of just one cat. Germ-line mutations sometimes happen.

-

The supposedly golden cat (which should be homozygous for the golden form) might be a very tarnished silver due to other genes it inherited alongside the dominant inhibitor (silver) gene.

-

There might be a second recessive form at the I locus, one that is recessive to both I (silver) and i (golden), but which produces a form of silver. In a breed where silver is not permitted, the occurrence of unexpected silvers might be due to a 3rd allele that is recessive to golden.

-

A hypostatic gene for silver that manifests only when epistatic (masking) genes are eliminated. An epistatic gene is “dominant” over genes on other chromosomes (an example is “dominant white” masking other colours). Likewise a hypostatic gene is “recessive” to genes on other chromosomes. (I use the terms dominant and recessive outside of their strict meaning here)

-

2 separately inherited gene pairs (different loci) interact to produce the visual effect of silver. When inherited separately there may be no visual effect or a different effect e.g. lightening of the coat colour (“powder coat”).

In North America there is a phenomenon in some breeds called "powder coat" and "high colour." A powder coat means a lighter colour cat while high colour indicates a darker colour. This reflects variations in depth of colour. It is seen in solid colours such as cream, lilac and blue, but descriptions of variations in tone have been mentioned by Soderbergh (1950s) and Frances Simpson (early 1900s), especially in blues and the variations are generally attributed to polygenes. The inheritance of powder coats is predictable. In some Burmilla and Burmese lines, powder coats have been linked to unexpected silver offspring (mismating was ruled out) leading some to wonder if the powder coat and a hypostatic silver are linked.

Whatever the actual genetics turn out to be - and whether there is a single Wide Band gene of a handful of polygenes - the Silver and Golden series are attractive cats in both longhair and shorthair varieties.

|